New York Times

6 September 2007

By PENELOPE GREEN

Winnie Lam was thinking about food when she made her Chocolate Sundae Toppings footstool, fashioned from a few bags of cotton pompoms hot-glued to an Ikea stool. “It came from staring into a bowl of ice cream one day,” said Ms. Lam, 31, who lives in Mountain View, Calif., and is a product manager at Google. “I’m a chocolate lover, but I’d rather look at it than eat it.”

Alex Csiky, a 43-year-old guitar maker in Windsor, Ontario, was focused, as he always is, on blowing a raspberry at the guitar-making industry while at the same time making a great sound when he built his sleek blond electric guitar from an Ikea pine tabletop.

Meanwhile, Christine Domanic, 28, an artist who was living at the time in Philadelphia, found the inspiration for her rolling bench in the sex ads in the back of city magazines. Her endearing Wiener Bench — a wooden bench festooned with fat pink crocheted tubes — was made from an old Ikea side table, the yarn from 60 used sweaters and the stuffing from a sofa left on her street on trash day.

Ms. Lam, Mr. Csiky and Ms. Domanic have never met but they are nonetheless related, connected by a global (and totally unofficial) collective known as the Ikea Hackers. Do-it-yourselfers and technogeeks, tinkerers, artists, crafters and product and furniture designers, the hackers are united only by their perspective, which looks upon an Ikea Billy bookcase or Lack table and sees not a finished object but raw material: a clean palette yearning to be embellished or repurposed. They make a subset of an expanding global D.I.Y. movement, itself a huge tent of philosophies and manifestoes including but not confined to anticonsumerism, antiglobalism, environmentalism and all-purpose iconoclasm.

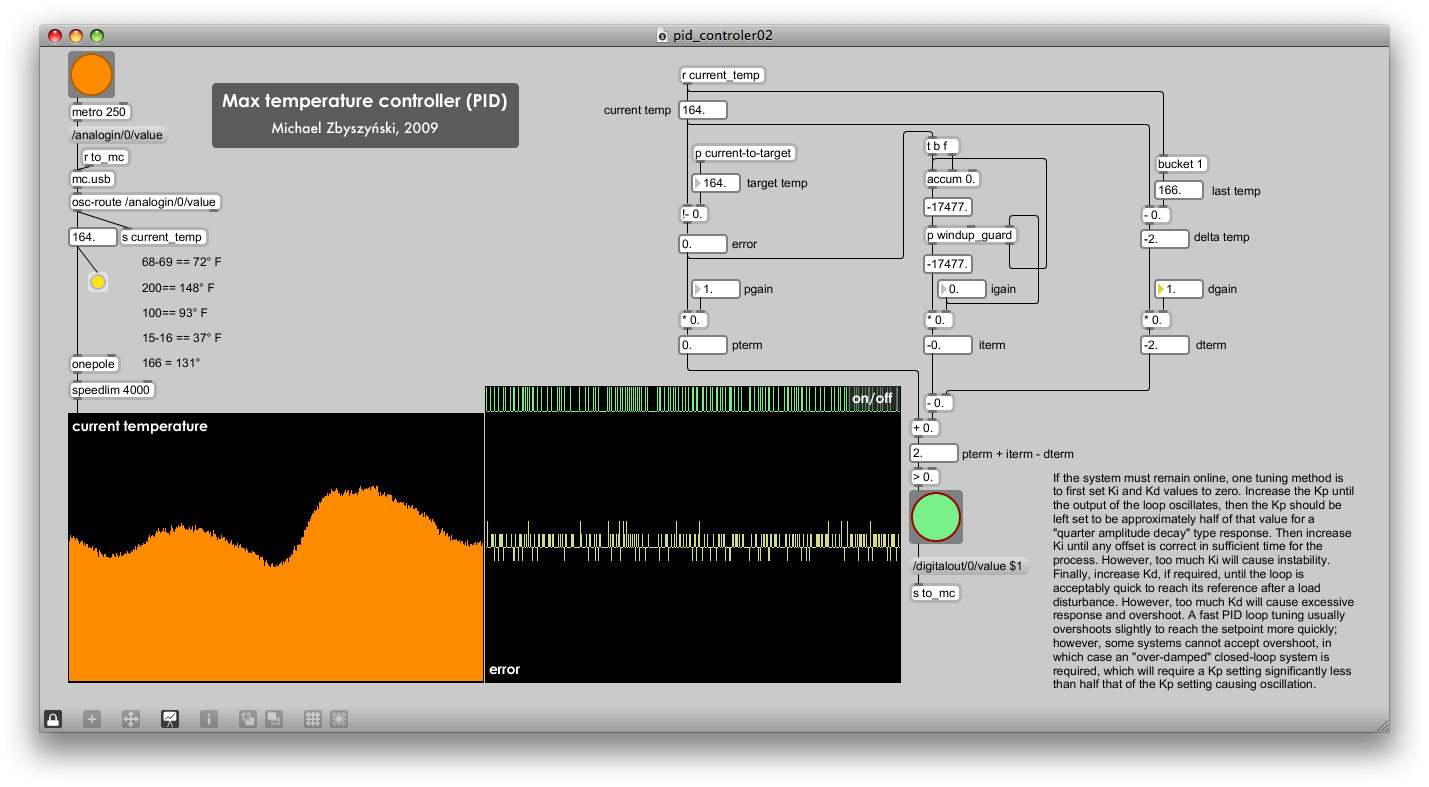

“I think there is a movement around looking at all the products that are available — this global stream of stuff — and realizing you can tinker with them and rebuild them,” said Michael F. Zbyszynski, 36, the assistant director of music composition and pedagogy at the Center for New Music and Audio Technologies at the University of California, Berkeley, whose own hack is a speaker array made from red plastic Ikea salad bowls, and who has made other musical objects from PVC plastic and coffee cans that “live in the zone of the hack,” he said.

“It’s all about not accepting what’s presented for sale as it is,” Mr. Zbyszynski said, “about not just doing a ‘paint by numbers’ of your life.”

The hackers have lately gained a salonnière in Mei Mei Yap, a 37-year-old Malaysian copywriter who lives in Kuala Lumpur and works for an advertising agency there. Ms. Yap, who calls herself Jules, for the Ikea chair she loves, and who has no affiliation with the mammoth Swedish furniture maker that makes it, is not, she said by phone from her apartment, particularly handy, but with her year-old blog, ikeahacker.blogspot.com, she has created a forum for those who are very handy indeed. With a keen eye and an open heart, Ms. Yap has built an encyclopedia of hacks by trawling craft and design Web sites and by inviting personal submissions.

Ms. Yap said she lives with a family of rapidly reproducing guppies and lots of Ikea furniture, but hardly any hacks. “Well, there are maybe three,” she said, describing a tower of wall cabinets, a side table made into a mobile home office unit, and a bathroom cabinet she added doors to. “But they don’t even qualify for my site.”

She presents hacks that are kitschy-useful, like Sara Madole’s bright green rolling cat litter box (Ikea hackers seem to be overwhelmingly cat people), which Ms. Madole, a 27-year-old law school graduate who lives in Houston, said she built from two Ikea Snack boxes. Ms. Yap also collects hacks that are meta in both concept and design, like the Nata Vintage chair — made by Anatomic Factory, a design collective in Florence, Italy — a Duchampian object that marries a walking cane with an Ikea chair.

“Nata vintage” — meaning, roughly, born vintage — “stems from a reflection on the eternal return of the ‘old’ as a recurrent tendency of the market,” Marco Popolo, one of the object’s designers, explained by e-mail. “Therefore let us make a provocation: what better way to sell a vintage chair than to borrow a walking stick (stereotype of the old) to replace a leg of a classic, stereotyped Ikea chair?”

Mr. Popolo wrote that he has been following Ms. Yap’s blog, which he called a “very interesting big container rich with ingenious and original ideas,” since its inception, drawn to the fact that it’s about “stuff made by common people” — as opposed to designers — who are trying to customize their lives. “This is a very contemporary phenomenon,” he said.

More prosaically, Ms. Yap said: “I think Ikea just makes it easy to D.I.Y. because it already has a system in place of mixing and matching this frame with that cabinet and those knobs. Hacking just takes it a little further, repurposing it to fit your needs. And maybe the geek-nerd in us hackers feels a buzz having outsmarted the Ikea system by creating something of our own.”

Some of the most ingenious hacks are as simple as a $6.99 Ikea desk lamp reimagined as a wall sconce, or stainless steel shelving reworked as a coffee table. The word hack is filched, as Shoshana Berger, editor in chief of ReadyMade magazine put it, from computer parlance, as in, “hacking into the mainframe.”

“The idea is you’re getting in through the backdoor,” Ms. Berger said, “and reinventing what’s there.”

In the 1990s, when Ms. Berger was a “cool hunter” at Y&R, the branding, marketing and advertising agency, “we used to call this ‘post-purchase product alteration, ’ ” she said, noting that Ikea hackers’ predecessors can be found in fashion, with the deconstruction movement fomented by the Belgians in the late ’80s, and in architecture.

“There is a long history of hacking industrial artifacts or found objects and turning them into high design,” she said, drawing a straight line from Buckminster Fuller to Lot-Ek, the Manhattan architectural firm that has played with cargo containers, industrial sinks and truck tanks. “But to my knowledge Ikea is the only company that is appealing to the do-it-yourselfer.”

Why Ikea, the 60-year-old megabrand whose perky Swedish style has homogenized living rooms from Europe to Malaysia (it now has 265 stores in 35 countries), should be so hackable has everything to do with its price point and, perhaps, its benign-seeming blondness.

There are hackers who have upended and truly subverted the happy Ikea message, like Guy Ben-Ner, an Israeli video artist who made a treehouse of Ikea furniture and an instructional video featuring a man who is a combination Robinson Crusoe, Jewish settler and Ikea salesman. The piece, which he showed at the 2005 Venice Biennial, was all about “the illusion of creating” that comes from the sort of D.I.Y. that regular Ikea shoppers practice, along with an attendant illusion of individuality. The Ikea-D.I.Y. promise is that “we shall all have, eventually, the same ‘private’ homes,” Mr. Ben-Ner said.

But most of the hackers Ms. Yap has collected aren’t perpetrating truly subversive acts. They are more focused on the pleasures of reinvention, and on modifying Ikea’s wares to suit their homes and personalities.

Mona Liss, director of public relations for Ikea in the United States, took her first look at Ms. Yap’s blog a few weeks ago, pointed there by this reporter. “I could spend all day looking at this,” she said, and then opined that what compels an Ikea hacker to hack, in addition to what she called Ikea’s clean palette, “is this invisible aura of Ikea, something in our DNA that is inviting and unspoken.”

“Being an Ikea worker,” she continued with animation, “I can tell you we’re a culture that’s asked to challenge conformity, to speak outside the box.”

Or outside the flat pack, as the company’s special packaging is called.

Ikea hacking reminded Ann Mack, 31, director of trend-spotting at JWT, the blue-chip advertising agency once known as J. Walter Thompson, of the way ad campaigns are spoofed on YouTube. “Customization is so huge for a demographic that’s skewing younger and younger,” she said. “They don’t want to be told by ‘the man’ what they should consume and how exactly they should consume it. That’s boring. They can make their own playlist. They can take a product and make it truly their own.”

In any case ReadyMade, Ms. Berger’s magazine, which she started in December 2001 and comes out every other month, was designed for hackers of all stripes. It’s a hybrid, part Martha Stewart, part Mrs. Beeton, for a reader who listens to the Silver Jews, reworks ads to display on YouTube and might turn rubbings of manhole covers into backlighted mandalas or repurpose an Ikea Billy shelf into a bed, following instructions that ran in the magazine in 2005 in an article called “Ikea Your Way.”

The magazine itself was a D.I.Y. project until last fall, when it was bought by the Meredith Corporation. Its success — it now has a circulation of 250,000 — has resulted in large part from the mind-set of a generation that came of age in the late 1980s and early ’90s with self-authoring tools, Ms. Berger said, “like editing their own movies and photos on their computers, blogging, creating their own Web sites.”

“They feel very capable and resourceful,” she said.

The rise of the computer culture, as resourceful as it is, means that “we are no longer a tactile culture,” Ms. Berger continued, “so there is this yearning for things that are hands-on and handmade.”

ReadyMade is part of a universe of D.I.Y. media and forums where Ikea hacks appear and are then found by Ms. Yap, who links her blog to them. It’s a universe that includes Make magazine (more science than design-geeky, for the handmade-robot set) and Web sites like instructables.com, which was created by M.I.T. Media Lab alumni as a forum for its users to share knowledge about how to make or do practically anything, including, as a glance at the home page the other day revealed, a quick banana nut bread and “hacking a toilet for free water.” Mr. Zbyszynski’s speaker array, with its goofy “Lost in Space” aesthetic, first appeared there.

The do-it-yourselfer’s agora is the two-year-old Etsy (etsy.com), run out of a 7,000-square-foot warehouse in Brooklyn by Robert Kalin, 27. He founded the site — an online community of 400,000 members, including crafters, designers and, inevitably, Ikea hackers — as an old-fashioned bazaar to sell handmade objects and promote “human-to-human contact,” as he described it. In July, Mr. Kalin said, Etsy sold its millionth item. “I don’t know if it’s anachronistic or ambitious,” he said, “but I just want to make everything I own.”

Mr. Kalin said that to him and his fellows at Etsy, Ikea is a natural resource. “We don’t look to a forest for wood,” he said. “We don’t want to use ‘new’ wood. We look at a Dumpster or an Ikea store as a place to go harvest ‘raw’ materials. It’s a very urban phenomenon: we have the resources we need and we have become expert at repurposing them, like taking these broken Ikea chairs and making them into a table.”

Mr. Kalin is big on “upcycling,” a process whose name was coined by William McDonough, an architect, and Michael Braungart, a chemist, in their 2002 book, “Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things.” They used the term to describe the process of taking something that’s essentially waste and moving it up the consumer-goods chain. “I love upcycling,” Mr. Kalin said. “I love this idea of bringing something from lower down and elevating it.”

Etsy held an upcycling contest last spring, inviting its users to make something of value out of materials that would otherwise end up on the trash heap. Christine Domanic’s Wiener Bench won first place. Last month, Ms. Domanic joined the Etsy staff as a marketplace coordinator, helping Mr. Kalin restructure the site. She has donated her bench to the Etsy lab.

“Anyone can come and see it,” she said. “It’s really comfortable and fun to scoot around the floor on.”